Moonshine

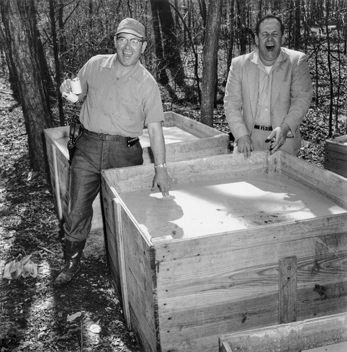

Moonsh ine, illegal, untaxed whiskey distilled by the “light of the Law enforcement officers test the evidence during a raid on an illegal liquor distillery in the Eno Township of Orange County in 1958. Photograph by Roland Giduz. North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library.moon,” has been a part of North Carolina lore and culture for centuries. From the state’s eastern swamps and pocosins to its remote mountain coves, no small number of North Carolinians have engaged in the manufacture of unbonded whiskey, which has also been called mountain dew, blockade, white liquor, white lightning, corn liquor, popskull, stumphole whiskey, forty-rod, and shine.

ine, illegal, untaxed whiskey distilled by the “light of the Law enforcement officers test the evidence during a raid on an illegal liquor distillery in the Eno Township of Orange County in 1958. Photograph by Roland Giduz. North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library.moon,” has been a part of North Carolina lore and culture for centuries. From the state’s eastern swamps and pocosins to its remote mountain coves, no small number of North Carolinians have engaged in the manufacture of unbonded whiskey, which has also been called mountain dew, blockade, white liquor, white lightning, corn liquor, popskull, stumphole whiskey, forty-rod, and shine.

Moonshining in the United States dates back to colonial days, but the industry’s most infamous period began with Prohibition in the 1920s and 1930s and continued after its repeal and the establishment of the alcohol tax. As time progressed, a vocabulary evolved around moonshining. The term “bootlegger” is said to have originated with the mandate against the sale of alcohol to Indians, when traders often concealed flasks of liquor in their boots to avoid detection. By the early twentieth century, a bootlegger was technically the seller of illegal alcohol, the moonshiner was the producer, and those who transported the product were called “runners” or “blockaders.” But often these duties overlapped, with moonshiners delivering their own products or runners selling some as well. Law enforcement officials attempting to stop moonshiners were nicknamed “revenuers.”

Despite the ban on the production and sale of liquor, there was a great deal of demand for it, and moonshiners did their best to meet that demand. Before Prohibition became law with the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919, bootleggers traveled regular routes like milkmen, going door to door delivering whiskey in saddlebags and hot water bottles. During the Prohibition era, Chicago was considered the center of illegal liquor activity. But the secluded stills of the rural South produced the life and legend most associated with moonshine, rising out of places such as Dawson County, Ga.; Cocke County, Tenn.; Franklin County, Va.; and Wilkes County, N.C.-once the self-proclaimed “Moonshine Capital of the World.”

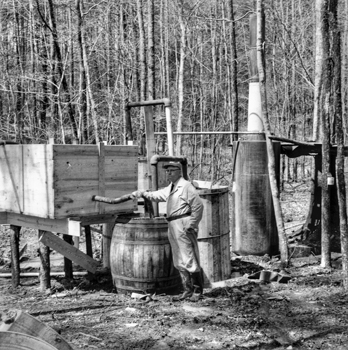

A law enforcement officer pauses after a raid on an illegal liquor distillery in the Eno Township of Orange County in 1958. Photograph by Roland Giduz. North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library.The key to any successful moonshine operation, besides a quality product, was a good car. Bootleggers modified their vehicles to get the best possible smuggling space and driving performance. Back seats were removed to make room for cases of liquor which, when loaded, would be covered with blankets. The 1929 Chevy touring cars could be refurbished with box-like traps underneath and a false back seat with a built-in door. These contraptions held 125 to 135 gallon jars of moonshine-all completely hidden. A few mechanics even converted their fuel tanks to “shine tanks,” hiding up to 35 gallons of whiskey in a false tank with the real fuel tank hidden under the floorboards. By the 1930s, space had given way to a preference for speed, and Fords became the vehicles of choice.

A law enforcement officer pauses after a raid on an illegal liquor distillery in the Eno Township of Orange County in 1958. Photograph by Roland Giduz. North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library.The key to any successful moonshine operation, besides a quality product, was a good car. Bootleggers modified their vehicles to get the best possible smuggling space and driving performance. Back seats were removed to make room for cases of liquor which, when loaded, would be covered with blankets. The 1929 Chevy touring cars could be refurbished with box-like traps underneath and a false back seat with a built-in door. These contraptions held 125 to 135 gallon jars of moonshine-all completely hidden. A few mechanics even converted their fuel tanks to “shine tanks,” hiding up to 35 gallons of whiskey in a false tank with the real fuel tank hidden under the floorboards. By the 1930s, space had given way to a preference for speed, and Fords became the vehicles of choice.

Moonshining was a highly profitable industry. If a bootlegger rounded a curve and spotted a revenuer roadblock, he might just jump from the car, leaving the agents to deal with the run-away auto and its illegal cargo. Moonshiners could lose every third car and shipment and still turn a profit. Federal agents, besides combing the countryside for moonshine stills, were forced to create new ways to combat the runners. Often the agents themselves drove cars they had confiscated from bootleggers. One inventive roadblock tactic was known as “spiking.” Several large nails would be embedded in a two-by-six board, and the agents would throw the “spikes” onto the road in the path of a moonshine car, shredding the tires and forcing the driver to stop.

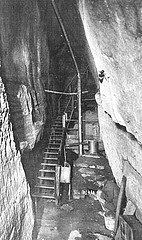

Moonshiner’s cave, no date, unknown location in North carolina. From the General Negative Collection, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC, call #: N_81_10_40.Despite the constant battle between the two, however, most moonshiners and revenuers were traditionally quite civil, even friendly, toward one another. Amos Owens, a resident of Cherry Mountain and legendary creator of the wildly popular “Cherry Bounce,” purportedly remained a gentleman despite being perhaps the most notorious moonshiner in the state. As legend has it, he once was discovered by revenuers (which he called “red-legged grasshoppers”) while preparing a shipment of his brew-three parts whiskey, one part cherry juice, one part sugar-and offered his captors breakfast. When they declined, he offered them some Cherry Bounce, which they drank happily. After several drinks, one officer staggered into the woods and disappeared for a few hours, while the other passed out in Owens’s house. Owens made no attempt to escape and waited patiently for the agents to regain their sobriety. When they did, they arrested Owens and took him to South Carolina, where he served six months in jail. The day after his release, Owens was back on Cherry Mountain, making whiskey and entertaining friends from miles around.

Moonshiner’s cave, no date, unknown location in North carolina. From the General Negative Collection, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC, call #: N_81_10_40.Despite the constant battle between the two, however, most moonshiners and revenuers were traditionally quite civil, even friendly, toward one another. Amos Owens, a resident of Cherry Mountain and legendary creator of the wildly popular “Cherry Bounce,” purportedly remained a gentleman despite being perhaps the most notorious moonshiner in the state. As legend has it, he once was discovered by revenuers (which he called “red-legged grasshoppers”) while preparing a shipment of his brew-three parts whiskey, one part cherry juice, one part sugar-and offered his captors breakfast. When they declined, he offered them some Cherry Bounce, which they drank happily. After several drinks, one officer staggered into the woods and disappeared for a few hours, while the other passed out in Owens’s house. Owens made no attempt to escape and waited patiently for the agents to regain their sobriety. When they did, they arrested Owens and took him to South Carolina, where he served six months in jail. The day after his release, Owens was back on Cherry Mountain, making whiskey and entertaining friends from miles around.

The lore surrounding moonshine eventually made its way into popular culture. North Carolina’s tradition of auto racing developed in the garages of bootleggers, particularly on the roads between North Wilkesboro and Charlotte. Legendary auto racers Junior Johnson and Curtis Turner were well-known bootleggers in the 1950s. Many of the winning entries at local Saturday night race events would be hauling illegal whiskey the following morning. Movies such as Thunder Road (1958), starring Robert Mitchum, and television series such as The Dukes of Hazzard offered both factual and fictional accounts of the exploits of moonshiners in the rural South. Moonshine Kate became wildly successful in Georgia in the late 1910s with songs such as “The Drinker’s Child,” paving the way for a niche industry of bootlegger songsters. The most famous was hard-drinking, three-fingered banjo player and renowned bootlegger Charlie Poole, who, with his North Carolina Ramblers, recorded a string of massively successful albums in the late 1920s, touting hits including “Take a Drink On Me” and “Good-bye Booze.” Poole died young, however, fittingly expiring in 1931 at the end of an epic bender.

There is a large body of literature regarding moonshine, one that is likely to increase in the twenty-first century as the actual practice of moonshining is supplanted by trafficking in other contraband and bootlegging recedes into the realms of romantic nostalgia. In reality, much illegal liquor was virtual poison, high in lead salts, although some excellent distillers undoubtedly came up through the moonshine ranks. Even by the early 2000s, Stokes County white liquor had found favor in the nonbackwoods, supposedly sophisticated Research Triangle area of central North Carolina.

References:

Joseph Earl Dabney, Mountain Spirits: A Chronicle of Corn Whiskey from King James’ Ulster Plantation to America’s Appalachians and the Moonshine Life (1974).

Wilbur R. Miller, Revenuers and Moonshiners: Enforcing Federal Liquor Law in the Mountain South, 1865-1900 (1991).

Bland Simpson, The Great Dismal: A Carolinian’s Swamp Memoir (1990).

Alec Wilkinson, Moonshine: A Life in Pursuit of White Liquor (1985).

Additional Resources:

Manning, Michael; Smith, Sarah; and Chernoff, Eric. “North Carolina Moonshine: A Survey of Moonshine Culture 1900-1930.” 1997. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Journalism. http://www.ibiblio.org/moonshine/index.html (accessed August 22, 2012).

Image Credit:

Moonshiner’s cave, no date, unknown location in North carolina. From the General Negative Collection, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC, call #: N_81_10_40. Available from https://www.flickr.com/photos/north-carolina-state-archives/2986098193/ (accessed July 9, 2012).

Cited from https://www.ncpedia.org/moonshine